There was much civil unrest due to poor pay and working conditions, and often the only option to quell riots was to bring in the Army, at the cost of civilian lives. Home Secretary Robert Peel’s solution was the peelers British police force.

The paid, professional police force would be recruited from ordinary men (not the upper classes) and be impartial and fair. They would police by consent, rather than military force, and only use force where absolutely necessary.

The first Lock-up matron was employed in 1895 to look after the female prisoners and take care of prisoner welfare needs.

These were the first women in the Birmingham Police with operational responsibility, walking the same landings that we now walk at the museum. The uniform was originally a simple black dress, with a white collar and cuffs. Later years saw a white pinafore over the dress.

The matrons would often spend time talking to the women, who sometimes desperately needed a kind word and a listening ear.

When Chief Constable Charles Haughton Rafter received approval to recruit two female officers in 1917, he chose two of the Lock-up Matrons for this important role.

Evelyn Miles and Rebecca Lipscombe were 54 and 63 years of age respectively. By 1918 Rebecca had come back to work at the Lock-up, but Evelyn continued a career that saw her become the force’s first female sergeant and oldest serving female officer, at 77 years of age by the time she retired.

Whilst all the auxiliary roles were important, and ensured policing continued during the war, the police messenger role is one that is often overlooked. It is hard to imagine the bravery required of a police messenger: how a boy of 16 with nothing but a tin helmet and a push bike, was expected to cycle around and take messages to officers on the ground or between stations or emergency services during air raids; with no street lighting as the black-out was in place, bombs dropping around him, people screaming, fires all over the places, telephone poles and other street furniture blown apart and causing hazards, to give but a brief description of the worst of their shifts.

Up until the mid-1800’s, the traffic in Birmingham consisted of horses and horse drawn vehicles which travelled at more or less the same speed, making things easily controllable. Runaway horses and carts and absent-minded pedestrians were the only cause of deaths on the roads.

As early as November 1839, police orders indicate the men of the Birmingham Police were to be fitted for capes.

It was made of a thick, felted woollen material and protected officers from the worst of the winter weather when out on patrol. Usually made of Melton cloth, it was fastened at the neck using a hook and chain, adorned with a pair of lion’s heads. The chain was made of a soft metal alloy, so that in an emergency it could be broken, thus preventing the officer from becoming entangled.

The great coat would be worn in winter, to keep warm on cold, dark night patrol. On really cold nights, a cape might also be worn over it. The great coat was made of heavy, wool-dyed indigo Devon kersey with black buttons embossed with the City coat of arms, movable silver letters, numbers and dots to identify the officer, a longer staff pocket in the left pleat and a whistle pocket between the third and fourth buttons. Loops were required on the sleeves to retain armlets.

Seven constables were formed into an initial horse patrol in 1840. In later years, the force would hire horses as and when they needed them, and there were always ex-military cavalrymen available to ride them for ceremonial duties, royal escorts and the like.

In 1923, after a few years negotiating ownership of horses with the Birmingham Corporation, Chief Constable Charles Haughton Rafter formed the Birmingham City Police Mounted Branch.

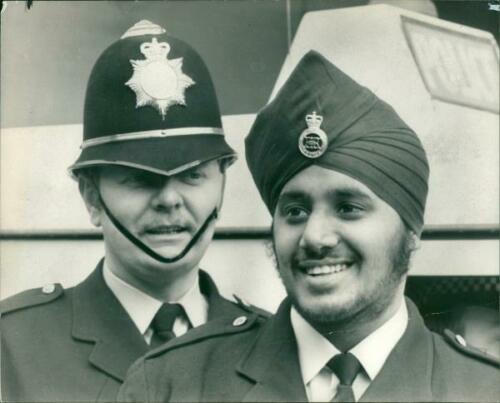

During the 1960s, Birmingham City Police recruited its first Black officer (Ralph Ramadhar) and its first Asian officer (Tariq Somra). This was the start of a more diverse police force.

During the 1970s, the Home Office was also considering how turban wearing Sikhs could be a part of emergency services that traditionally wore helmets. In the West Midlands our first officers to wear turbans were special constables Mohan Singh and Pervinder Singh Chodha in 1975. Surjit Singh Sihota was the first regular officer to wear a turban, joining the force in 1978.

The turban at the time was a choice of black or blue with West Midlands Police overwhelmingly selecting black. The style has not changed and is all preference. A West Midlands Police cap badge would be slotted onto the front of the turban and removed when the officer is not on duty.

Eventually officers were given the option to choose whether or not they wear the badge. The reason behind the badge becoming optional is that the turban belongs to the Sikhs and is their crown. The badge depicts the crown (sovereign) and so some people consider the turban is being incorrectly labelled as being that of the establishment.

They started being posted out onto division rather than just being based in the dedicated Police Women’s Department. Women could now remain with the police after getting married, although in line with wider society, most women still left employment once married or pregnant. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that it started to become common for policewomen to return to work after maternity leave.

It wasn’t until the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act that women were no longer prevented from taking up specialist roles like dog handler and mounted officer.

Policewomen wore a pleated skirt, white shirts and fitted tunic. Throughout the 1960s to 1990s they went through a variety of different styles of hat including hostess and pill box, before finally bowler hats were issued in the late 1980s.

By the 1980s women were able to wear NATO jumpers or cardigans which were more comfortable and practical, but continued to wear tunics for court and other occasions. After a brief, failed, trial of culottes during the 1990s, by the early 2000s women were no longer issued with skirts and had completely switched over to trousers.

Female officers were issued with a handbag and a small truncheon, which was often the subject of ridicule.

Before it was introduced in West Midlands Police, many officers were already starting to fear for their own safety and had invested in their own body armour. Sometimes covert options that went under their shirt, to give them peace of mind.

During the miners’ strikes of 1984-1985, women pretty much ran the police stations across the West Midlands on 12 hour shifts, whilst male officers went on mutual aid to support the local forces.

Policing 50 years ago looked very different to how it does today. Officers wore smart tunics, light blue shirts and highly polished shoes.

Female officers wore skirts, white shirts and carried a police issue handbag. The only protection officers had out on the streets was a truncheon and a radio.